West Lake Reflections: in defence of humidity

also: on transcendent sightseeing, and the end of youth

I hate humidity. I half-joke that my happiness is negatively correlated to the percentage of humidity in the air— below 70%: happy, 80% and above: annoyed, 90% and above: practically morose.

Apart from a few golden crisp months every winter, Hong Kong is, genetically, a humid place. In spring, the fog moves in and settles into the city. Everything is wet and damp— the pavement, laundry and your bath towel, still limp and wet from using it the day before. The dehumidifier is your best friend in this season, and lobbies of buildings and train stations blast ventilation fans in a futile effort to dry the slippery floors.1

I went to Hangzhou recently and found that its beauty lies in its humidity.

It rained incessantly during the trip; not a thunderstorm, but a gentle 24-hour dripping that formed part of the atmosphere. The humid fog left a film of moisture on my skin and blurred the mountains in the distance, and I realised there’s a reason 山水畫 shan shui hua, literally, “mountain water art” was cultivated in China and is a revered genre of painting here; the climate almost begs for it to happen.

These paintings, painted in the Song Dynasty around 1000 years ago, are just a small specimen of the body of mountain-water art over the centuries. Apparently, our ancestors also lived in such misty, foggy climes and learnt to appreciate the weather.

Ancient poetry also speak of similar scenery (all translations are mine unless otherwise stated, please feel free to point out any corrections)—

興來每獨往,勝事空自知 xing lai mei du wang, sheng shi kong zi zhi

行到水窮處,坐看雲起時 xing dao shui qiong chu, zuo kan yun qi shi

《王維• 終南別業》

I walk alone when it pleases me, and experience small victories only the air and I know

I walk until where the water ends, and sit and watch the clouds rise2

- Wang Wei, My Retreat in the Zhongnan Mountains

How important is terrain or climate in the art and philosophy of a region?

Here is what John Berger has to say in Portraits regarding the relationship of the desert to Islamic art, literature, philosophy:

Why is the knife so true to this land? The blade was a reminder of the thinness of life. And the thinness comes, very materially, from the closeness in the desert between sky and land. Between the two there is just the height for a horseman to ride or a palm to grow. No more. Existence is reduced to the narrowest seam… Within this awareness there is a fatalism and intense emotion… a passionate protest against naming anything sacred except God.’ 3

There’s a truth in this that can’t be argued by logic but sort of makes sense in an osmotic, ahhhh kind of way. The knife-edge of sky and sand mean all in or nothing. Whereas the misty rolling hills of China, with water in the sky, air, and rivers, birth fluid philosophies like Taoism, where the Dao or “the way”, is to go with flow and the harmony of natural order and not to do things that are in conflict with nature.

I’m not saying that it is because of terrain and climate that these specific philosophies and art have emerged in these particular regions— it may never be possible to pin these threads of creation to one, or even ten, reasons. I’m saying that climate is one influencing factor that’s often overlooked.

Because like it or not, weather and terrain influence us. The mist engulfs our souls, humidity sticks to our skin, dryness cracks our lips, heat lulls us to sleep, and balmy breezes mellow us and set our temperaments.

The people in Hangzhou don’t blast away the humidity with a dehumidifier. The West Lake in Hangzhou, everyone knows, is most charming on a rainy day, when mists blur the receding mountains like sequentially diluted brushstrokes. Romance happens with arms hooked and faces covered under umbrellas. Vegetation is more lush dripping with water, and peace is deeper indoors when you hear the ASMR drip of the rain outside. It is pale femininity, soft scenery and even softer bed linen. It is a mentality of finding beauty in your surroundings, not wishing for a better weather, that I hope to bring back with me to Hong Kong. For if we attack the mist with dehumidifiers and air-conditioning, when will we ever get to see the clouds rise?

Tourism in China - an exercise in transcendence

Sightseeing in China is a bit different from sightseeing in other places.

The sights are dwarfed by the crowds. Weather is usually fair, at best, and greys a lot of the sights. You jump in and grab a few photos when you spot a gap in the crowd then you are driven along again by the throng of people about you.

Enjoying yourself is a little bit of an exercise in transcendence. You need to look above the heads of the people and recite some poem that was written about the place or bring to mind its historical significance to add a depth to your experience that wouldn’t otherwise be there.

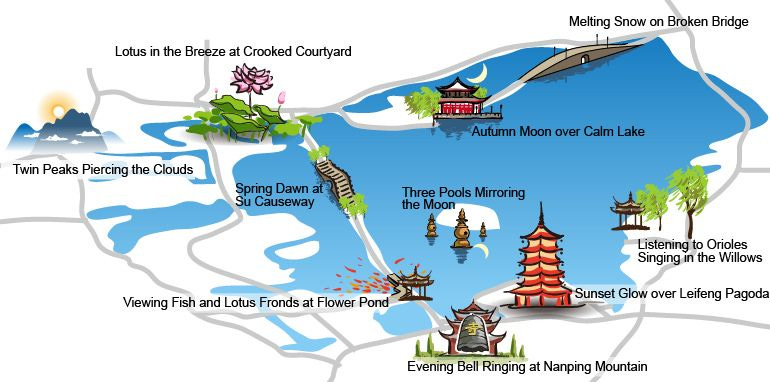

For example, here is the famous West Lake (西湖) in Hangzhou and all the areas of significance the place contains. Each sight, in Chinese, is a four-letter poetic phrase, and has either a legend or some historical significance behind it.

Su Dong Po (Su Shi)

It wouldn’t be complete to talk about Hangzhou, a place sustained and nourished by art, without mentioning Su Dong Po (蘇東坡), or Su Shi (蘇軾) (his official name), possibly one of my favourite poets of all time.

He was a poet and statesman in the Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127) and was a governor of Hangzhou at one point in his life, building the Su Causeway at West Lake and writing poetry about the place.

I hadn’t really seriously read Chinese literature before, except when we were forced to learn Tang poems in school (all of them, in my mind, read in a snotty kid’s voice).

I appreciated literature in English before Chinese— I fell in love with Keats, wrestled with Shakespeare, tasted Pablo Neruda and saw myself in Emily Dickinson, and, for the longest time, thought I was in love with the English language, before I realised what I loved was poetry and the artful mastery of language itself, not which language it was written in. Or rather, I loved poetry no matter what language it was written in, but because English was the medium most readily understandable to me, I loved poetry in English.

Reading Su Dong Po was the first time I learnt to love poetry in a different language. His poems were called 詞 ci lit. “lyrics” because most poems written during this era were lyrics to songs (of which the melody is long lost today).

One of his poems is immortalised this Teresa Teng song, which is often bandied about in group chats during Mid Autumn Festival:

Imagine seeing your name on the credits for song lyricist written a thousand years after you’d lived. Now that’s some #lifegoals right there.

I could go on about how I love that poem, or another, but for today, I will share this one with you, which describes a scene in a village at the end of spring—4

花褪殘紅青杏小。燕子飛時,綠水人家繞。枝上柳綿吹又少。天涯何處無芳草!

牆裡鞦韆牆外道。牆外行人,牆裡佳人笑。笑漸不聞聲漸悄。多情卻被無情惱

《 蝶恋花·春景》

Red flowers fade and small green apricots grow

When swallows fly, green water of the river flows around the village

The little remaining catkins on the willow branches are blown away by the wind

But wherever you look, green grass stretches all the way into the horizon!

Inside the walls of a residence, someone is swinging on a swing. I walk past outside, and hear sweet peal of laughter inside.

The girl’s laughter fades away and I can’t hear it any more; I’m left standing outside, in longing.

- Butterfly in love with a flower, Spring Scenes

Though technically he didn’t write this piece in Hangzhou, I could feel fragments of these words float around as I walked through the city, much of which has retained a very classical form of architecture, an aesthetic not dissimilar to when he lived around a thousand years ago.

Let’s get into the poem—

枝上柳綿吹又少。天涯何處無芳草

The little remaining catkins on the willow branches are blown away by the wind

But wherever you look, green grass stretches all the way into the horizon!

Describing the end of spring and the beginning of summer, these pair of lines is often used to console those who are experiencing heartbreak— though you’ve lost someone (a catkin on the willow), look, there are so many other people out there (green grass) that can be the right one for you; i.e. there are so many other fish in the sea.

Su Dong Po, to the best of my knowledge, never explicitly stated these lines were about heartbreak. The beauty of poetry is that we can interpret it how we will, and to me, not experiencing heartbreak at the moment but standing of the edge of youth, these lines console me in my current season of life. Though I’m at the tail end of youth, infinite possibilities, like wild grass, stretch unfettered all the way into the horizon in the summer of our lives.

牆裡鞦韆牆外道。牆外行人,牆裡佳人笑。笑漸不聞聲漸悄。多情卻被無情惱

Inside the walls of a residence, someone is swinging on a swing. I walk past outside, and hear sweet peal of laughter inside.

The girl’s laughter fades away and I can’t hear it any more; I’m left standing outside, in longing.

The swing, the laughter, the person left in longing outside— its a line that’s so alive and so immediate, that I almost don’t want to posture or analyse it for fear of breaking the spontaneity of the scene, and leave the scene, pregnant with emotion as it is, in your mind.

In Hangzhou, art and poetry infuse the environment with a beauty and contextual depth that makes you appreciate your surroundings more as you walk by the lake and through the small alleyways. Sometimes I wonder, who needs virtual reality when we already have the extra dimension of Su Dong Po?

Thank you for reading!

Special thanks to

and for providing feedback on the piece.(Foot)notes and Recs 🌿

I am of course merely quoting something I’ve read of whose opinion is not my own— I am no expert on the matter.

For those who like enjoy poetry in the context of travel or in personal memoir,

does a fantastic job over at his substack. I especially enjoyed these posts—

Your essay is such a fun surprise also in that I was having a conversation with somebody a few hours ago that I should see her in Hangzhou. By the way, "勝事空自知" is such a tricky line to translate, isn't it? "勝事" means a happy occurence, and I believe it refers to the scenery which the poetic narrator gets to enjoy by himself. I like it that you interpretated it as "small victories". Meanwhile, it seems "空" here does not mean air in this poem. As 自 is often an adverb, not a (pro)noun, I think "空" must be an adverb too, describing the manner in which he perceives(知) the "勝事". In other words, he perceives it on his own and in a disinterested manner.

Hey Clare,

This was the first story I've read on your Substack and man, what a feeling. You write so softly, so poignantly, in a way I can taste all the delicious details and your sinewy bits of thought poured into it.

Anyway, thank you for this beautiful piece. It left me feeling like how it feels like watching the credits roll after a damn good movie. You just sit there, reeling. At the end of this, I was thinking to myself: It *is* possible to feel strangely connected to a stranger, just through her writing alone. You've created a beautiful world in this story and I'm grateful to have dwelled in it, even for awhile.

Thanks <3