Writing letters for the illiterate (part 1)

Part 1

If you were born a few hundred years ago, what job do you think you’ll be doing?

I’d like to be a poet or a hot young scholar looking suave yet principled swooping off on a midnight mission somewhere—

But, realistically, if I were born in a similar socio-economic class and have the same constitution that I do now— my less-than-noble bloodline would land me in merchant or peasant class, but lacking the savviness of a merchant or the physical strength of a peasant, and being the bookish, myopic sort, I know exactly what I would be doing— holed up in a corner stall somewhere, writing letters for the illiterate.1

Called 代寫信 dai xie xin in Chinese, literally ‘helping people in their stead’ to write letters, this was very common all over China for the past hundreds of years.

In the early and mid 20th century, this was a well-documented phenomenon in Hong Kong too.

With the economic growth of Hong Kong in the 1960s-80s, many blue-collar migrants came to Hong Kong from Mainland China or Southeast Asia as factory or labour workers, and many of them would want to write letters back home. Many of these workers were illiterate, and would need to seek the services of a letter writer to help them convey their thoughts into a letter. The usual practice was, after the letter was written, it would then be read out, and if the content was approved by the customer, the letter would be sealed. Market rate was $10 HKD (~$1.3 USD) an A4 page in the 1960s (Source here).2

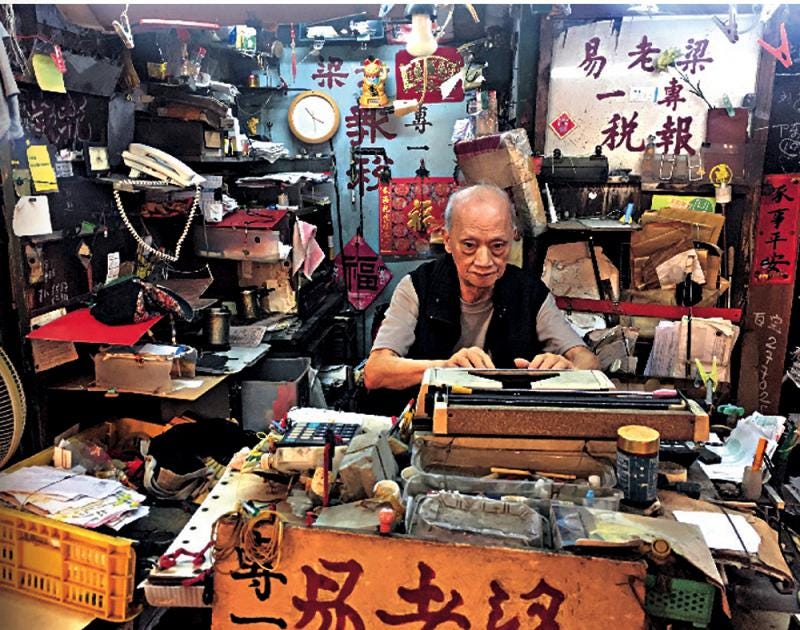

Apart from writing letters, there were services for other types of paperwork as well. The Chinese characters in the picture above list the types of services the stall offers, among which include: letter writing, writing business cards, applying for licenses, signage, and, at the end “all sorts of documents”.

Many of these letter-writers were retired teachers or clerks. Most of these letter writing stalls were gathered near post offices, and, at their peak in the 1960s, there were about 40 such letter writing stalls near the Yau Ma Tei post office.

In 1979, 9 years of schooling was made mandatory in Hong Kong, and, as literacy rates climbed, demand for letter writing services gradually dwindled down, and in the past 10 years, the few remaining stores have moved into the Jade Market in Yau Ma Tei.

In memory of the migrant workers who come here to do backbreaking, dogsbody work,3 and to the people who listen to their stories, I want to summarise and translate an excerpt from the following articles from Takungpao and Chinanews.cn (both written in 2019) for you today, which interview a letter writer based in Jade Market in Yau Ma Tei. (The source articles are here and here)

At his store Leung Lo Yee, Chan Kau, now 77 years old, sits at his typewriter waiting for customers. Providing letter writing and tax filing services, he has been working at the store for over 40 years.

Uncle Kau is a Chinese-Vietnamese who is fluent in four languages— English, Chinese, Vietnamese and French. After working in accounting in an American film company in Vietnam, he came to Hong Kong in the 1970s, where he originally worked as a bartender before setting up his letter writing business.

The majority of his customers were migrants from Mainland China or Southeast Asia. “In these letters, usually, customers would ask about how their family members are doing, and only report the good news and not the bad news.” Sometimes, customers would cry and get so upset telling Uncle Kau their problems that he would have to turn them down.

Some of his regular clients patronised his store for over 10 years. Even up until the 1970s, because long distance phone calls were expensive, some clients would come as they preferred to write letters as correspondence instead. Some letters were written in English, some in Chinese.

As he’d known his regular customers for a long time, Uncle Kau would be familiar with many of their personal matters. “I know many of their family matters, but I keep them confidential,” he says, as a principle of his profession.

Uncle Kau’s hearing has worsened in recent years and his gait is less agile than before, but he still goes to work every day.

“As long as my physical condition allows it, I will taking care of this store,” he says.

Out of curiosity, we decided to visit Jade Market to take a look.

The only letter writing stores we found were boarded up and closed, maybe closed for the weekend, or perhaps only open on an ad-hoc basis.

The domain of their services have shrunk to the practical needs of today, which include (from the picture above): tax filing services for shopkeepers, delivery workers, taxi and minibus drivers, filling in passport forms, and translating documents.

Stay tuned for part 2…

Were there similar jobs in your country before? Drop a comment below and say hi!

🀅 Footnotes and Recs 🀅

This would be if I was born a male. Of course, if I was born a female, I would just be squatting in a backyard somewhere, scrubbing the laundry.

For those who are interested in life as a migrant in Hong Kong in the 1970s and 1980s, Louisa Wah’s memoir-ish is a fascinating read.

Heidi Tai’s article on the Chinese restaurant Super Bowl closing is a moving dedication to the immigrant working class spirit. I’m a big stickler of clean floors and I gripe a lot about the floors of restaurants, so this line in particular stuck to me— “Every surface from the table tops to the floors would be clothed with a subtle film of stickiness. You have to be Chinese to understand that such memories are a form of high praise. The stickier the floors, the better the food!”

I loved this post. Since you asked, here is my brush with letter-writing:

I grew up in Mumbai during the 1960s. My decidedly middle-class family had a "servant" - a full-time helper who lived on the edges of our very basic lives. He was 100% illiterate.

Starting when I was about ten, my mother would ask me to be the scribe, writing letters in my neat schoolgirl handwriting as dictated by him. All the letters were to his wife who lived in a village far from any highway or electricity. She would also have to have someone read the letters to her. The content was basic: I am sending xxx money to you, how is the (subsistence level/sharecropping) farm doing? I am well, hope you are too.

With an imagination activated by Bollywood movies, I would add a line or two of my own. "I miss you," I would write. When I would read the letter back to him, he would smile sheepishly.

This is one of my more vivid (and painful) memories from childhood. I trace my emerging awareness of inequality, injustice, etc to my empathy for him and sadness for his hardscrabble life. (Echoes of the short story titled Kabuliwalla by Rabindranath Tagore.)

Currently learning how to read Chinese, so I probably need their services!

We take literacy for granted these days, and I'm glad most Chinese are literate in China these days. Outside of her, however, many of the diaspora struggle with Chinese literacy ;P

A fascinating look at an old service that has existed for centuries.