I’d always thought we were born into culture; that values, language and flavours seep into us by osmosis, shaping our countenance, what we laugh at, and sink into our DNA by the time we gain rational thought.

But I got married earlier this year and through the process, realised that culture is a lifelong learning process. Wedding planning was learning about what our ancestors valued (tradition), what we valued, what our families valued, and meeting in the middle. It was learning about small diasporic, generational and regional differences leading to larger arguments, and seeing the fingers of history entwine themselves in the rituals of the present.

I won’t talk about all aspects of a wedding here. But! Because I love words, and belivthe words we use say so much about who we are, I will talk about wedding invitations.

Usually, in local Hong Kong weddings, there are two invitations— one in Chinese and one in English; English for friends and the younger generation, and Chinese for relatives.

The English ones follow conventional style, with the bride and groom doing the inviting. Here’s an example of one—

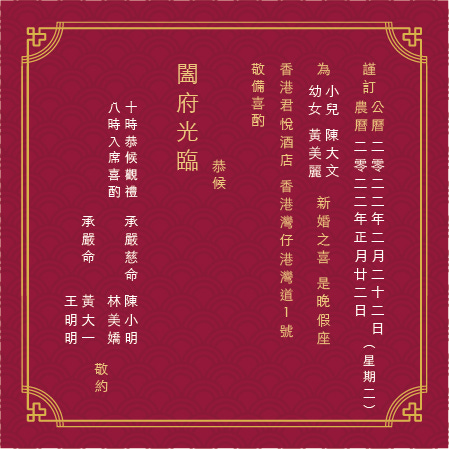

This is an example of a Hong Kong style Chinese wedding invitation:

Let’s translate it first.

To write one, one first has to understand it, which is no simple feat, even for Chinese native speakers. The language is archaic and not used in modern writing or speech. But no matter which printing company you go to, the wedding invite is worded and structured in exactly the same way, with guides online even listing rules to follow when penning an invite, and what not to get wrong.

A Dissection of Coded Confucianism

The Sun, the Moon, and the alignment of the stars

I never cared about the Lunar Calendar much, only referring to it during Lunar New Year or on Chinese festival dates. But some of the older generation in China remember their birthdays by the Lunar Calendar, which makes figuring out when to celebrate them not as simple as setting a recurring Google Calendar event.

In ancient China (and also not uncommonly amongst Chinese couples today), the Lunar birth dates of bride and groom are given to an astrologer to see if they match as a couple, and to select a suitable wedding date. There are even apps for these nowadays.

There are set terms to call the bride and groom depending on their birth order in the family and the number of siblings they have, and it gets very technical.

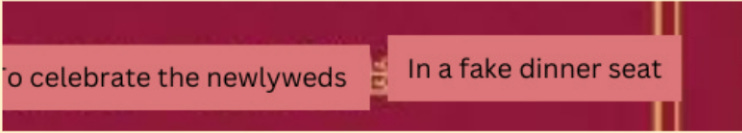

Can I actually sit on those chairs? The humble servant and the “fake dinner seat”

假座 (jiǎ zuò) is an archaic term to mean that the venue you use for the wedding dinner is not your house but a borrowed (“fake”) venue of a restaurant, a hotel, etc. There’s also the tone running throughout the invite that the hosts are putting themselves in a very humble position (i.e. sorry about my fake venue!) and their guests on a pedestal, something very common in ancient China, which might be familiar to those who’ve watched any ancient Chinese dramas (!)

The invitation is worded so that the parents are inviting their guests to their children’s wedding. Understandable, considering in ancient China Confucianism. filial piety, etc etc. is a way of life instead of a philosophical term, and that marriages then were arranged by parents between their mostly teenaged children.

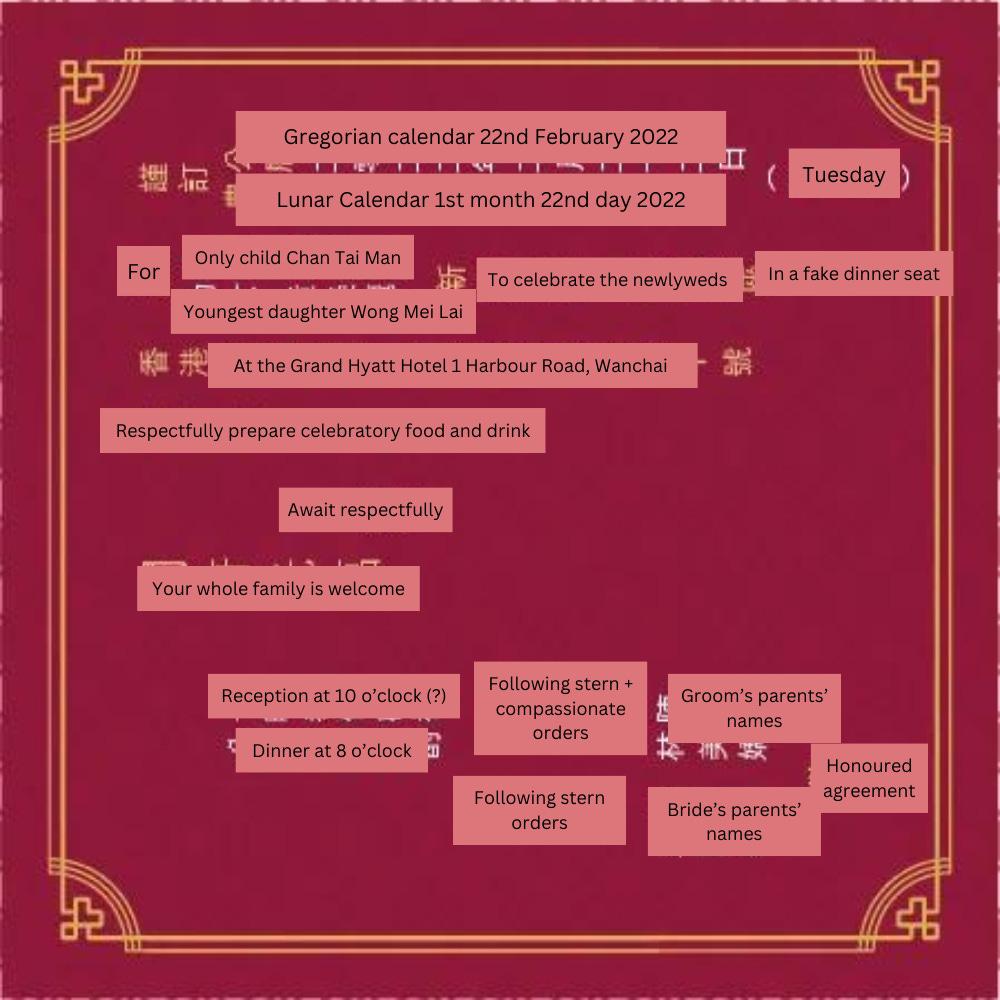

Question: Can you figure out whose grandparents are still alive from the screencap below?

Answer: you can!!

Following grandparents’ orders - children obeying parents obeying parents

The first four Chinese characters, the phrase “乘…命” (chéng…..mìng) means to execute (or literally “ride on”) someone’s orders.

The two middle words are stand-ins for “father” and “mother”.

“嚴” (yán) means “strict” or “severe”, and here is used to denote father. In the context of the wedding invite, this is the groom/bride’s father’s father, i.e. the paternal grandfather.

“慈” (cí) means “compassionate” or “kind” and used to denote mother. In the context of the wedding invite, this is the groom/bride’s father’s mother, i.e. the paternal grandmother.

How compassionate came to mean “mother” and strict became a stand-in for “father” probably originated from the phrase yan fu ci mu (嚴父慈母), lit. “ strict father and compassionate mother”. The origins of this phrase come all the way from the Jin dynasty (266-420 C.E.) “納誨於嚴父慈母”, or “I received my teachings from a strict father and a kind mother”.

So, if the parents are heeding “strict and compassionate orders”, it means both paternal grandmother and grandfather are still alive.

If they are heeding “strict orders” only, it means that only the paternal grandfather is still alive.

If they are heeding “compassionate orders” only, it means that only the paternal grandmother is still alive.

And if nothing is written as a prefix before the parents’ names, it means both paternal grandparents are deceased.

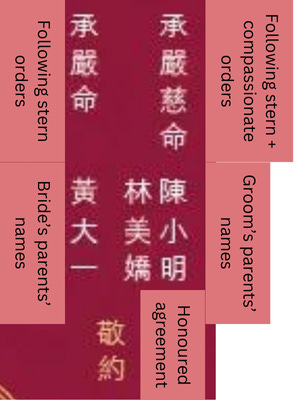

Let’s a take a look at our example below then–

The groom’s parents here are following “stern and compassionate orders”, so we know that both paternal grandparents of the groom are still alive. As the bride’s parents are only following “compassionate orders”, only the paternal grandmother of the bride is still around.

Did anyone back then want to know about the maternal grandparents? It goes without saying that ancient Chinese society, like many ancient societies, was highly patriarchal.

Diasporic variants?

My parents requested to put their names on the English invitation. As in, “[mother and father of bride] and [mother and father of groom] invite you to attend the wedding ceremony of their children…”

“But your names are already on the Chinese one. You already did all the inviting in the Chinese one.” I said. “In the English invite, the inviting is done by me and the fiancé.”

“But we can’t read it! And neither can our friends!” my mom retorted.1

My parents are ethnically Chinese but are from Malaysia. And sure enough, doing a quick search of Malaysian and Singaporean wedding invites, wedding invites were formatted as thus:

With the parents’ names included and doing the inviting. As my mom succinctly said, “we are still Chinese following Chinese traditions, but in English.”

This was the Chinese version of our wedding invite in the end! The thing that looks like a red seal on the right is the word “囍“, “喜“ xi meaning something joyous or happy, and because a wedding is the bringing together of two individuals, it is double the happiness, “囍”2, a character which kind looks like two people holding hands.

A few of our Mainland Chinese friends pointed out they’d never seen this style of writing before in Mainland Chinese e-wedding invites, which are usually written in straightforward, modern Chinese and sent on Wechat (the Chinese equivalent of Whatsapp). Wedding invites in Taiwan are also relatively straightforward and free of family tree insinuations.

Why has this archaic document prevailed here? I suppose this little cultural niche of Hong Kong’s was undisturbed by our former British colonisers or the political and cultural upheavals of 20th century Mainland China. Hence, thanks to innumerable generations of didactic parents, the exact words of this ancient text have survived to this day.

In some respects, it documents the spirit of our wedding– old traditions, new bonds.

Thank you for reading Slow Burn Living!

Also a big thanks to lovely friends and who helped make this essay sound less like the index pages of a textbook and more like a post ^^”

Drop a note and say hello in the comments! I would love to know: ☕

What are wedding invites in your country like, if you’ve ever received them or had to design one? When was the last time you’ve learnt something about your own culture without deliberately setting out to do so?

Footnotes and Recommendations

As a minority group, many Chinese growing up in Malaysia would have attended schools which taught Malay (the national language) and English. Chinese might be taught, but hardly to reading/writing proficiency. For that, one would have to go to a Chinese-medium school.

goes into detail about education and languages in Malaysia in this fantastic post.For those who are interested,

does personal memoirs around a Chinese character or a specific phrase.

When people ask me why the Chinese diaspora seemed to be able to retain their culture despite centuries away from the mainland, I explain that our culture is literally hard coded into our language, mindsets and values. This illustration of how a wedding invitation reflects various Chinese beliefs is such a great illustration!

Thanks for breaking this down! I now wonder what happened with my own wedding, haha. My husband and I sent out the English invites. I wonder what my in laws' friends got...

Very cool post!